It seems appropriate that I discovered Emily Dickinson’s poetry when I was skipping Sunday school by ducking into a small library at the church we attended when I was young. I took a small, slender volume of Dickinson’s poetry from off the shelf and opened it to a page where I read:

I'm Nobody! Who are you? Are you Nobody too? Then there's a pair of us! - don't tell!

With that single poem, I felt she was my own secret friend and confidant. As someone who was a questioner and never felt I truly belonged within the church, I found in Dickinson my own kind of saint, one who wrote of her questions, her doubts, her ever-changing sense of spirituality. Her poems were intense, enigmatic, full of life; all the while contemplating death and whether or not there’s a God or an afterlife. She never explained, never offered easy answers, never shied away from confronting pain, dread and death. She always told me the truth, even when she told it “slant.”

Dickinson’s poems have been a touchstone and guiding star throughout my life. For years, I have longed to make a spiritual pilgrimage to her home in Amherst. This year I finally did. I spent two days in Amherst and, on both of them, I went to her house. On the first one, I just walked the grounds and garden. No sooner had I walked among the old oaks and the garden, I found myself overcome with emotion. It was such that I had to sit down on a bench to compose myself. This was the garden that she had loved and tended ever since she was a girl. I thought of the letter she wrote when she was only twelve, “My Plants grow beautifully…” Or that she described herself as a “lunatic on bulbs.” She loved lilies, crocuses, fritillaries, hyacinths, and daffodils.

This was the garden that meant so much to her that she had it written in her funeral specifications that the funeral party was to circle around her garden and then go through a field of buttercups to West Cemetery where she was buried. As I sat there on that bench, I spotted a red-winged blackbird, a cabbage-white butterfly flitting about, an orchard oriole, and a bee drinking nectar from the flowers. The latter made me think of her poem:

"The lovely flowers embarrass me. They make me regret I am not a bee...”

I heard the sound of a bobolink in the trees. This was a bird she mentioned at least twelve times in her poetry. Just being here brought tears to my eyes. All around me was the world of her poems, the world that inhabited her imagination to such a degree and depth that one could not help but feel the profundity of every small detail around me. She made me see.

As I walked, I found an oak leaf on the path. It came from an oak that had been on the property since Emily herself was alive. I picked it up and placed it in my journal. I also collect small stones wherever I travel, so I picked up one I found on the grounds. I would also collect one from her grave.

Being here was like stepping into her poetry that had so shaped and guided me. As the novelist Helen Oyeyemi said of Dickinson, “Somehow she had this startling perspective that drew her out of an externally "small" life of house-keeping and gardening and cakes and conversation and enabled her to flirt with the infinite.”

The next morning, before I took a tour of Dickinson’s Homestead, I visited her grave in West Cemetery. On the headstone were offerings of pens, pencils, stones (some painted), notes, small poems, and seashells. Each laid there to pay respect to the “myth of Amherst” as she was often referred. It was quiet, save birdsong, which seemed appropriate for a poet who references birds in at least 222 of her poems. I thought of how her last words were, “I must go in; the fog is rising.” I thought of how I was a year older than she was when she died.

Standing there, I found myself reciting one of her poems:

I heard a Fly buzz - when I died - The Stillness in the Room Was like the Stillness in the Air - Between the Heaves of Storm - The Eyes around - had wrung them dry - And Breaths were gathering firm For that last Onset - when the King Be witnessed - in the Room - I willed my Keepsakes - Signed away What portion of me be Assignable - and then it was There interposed a Fly - With Blue - uncertain - stumbling Buzz - Between the light - and me - And then the Windows failed - and then I could not see to see - I thought of her use of dashes, which is used because dashes are known for their ambiguity. Dickinson was never one for obvious clarity. Dashes that caused the reader to pause. So many of her letters and poems are tied to my having listened to a recording of Julie Harris reading a selection of them.

Before I left, I left my own tribute to a poet who’d been a north start for me throughout the years.

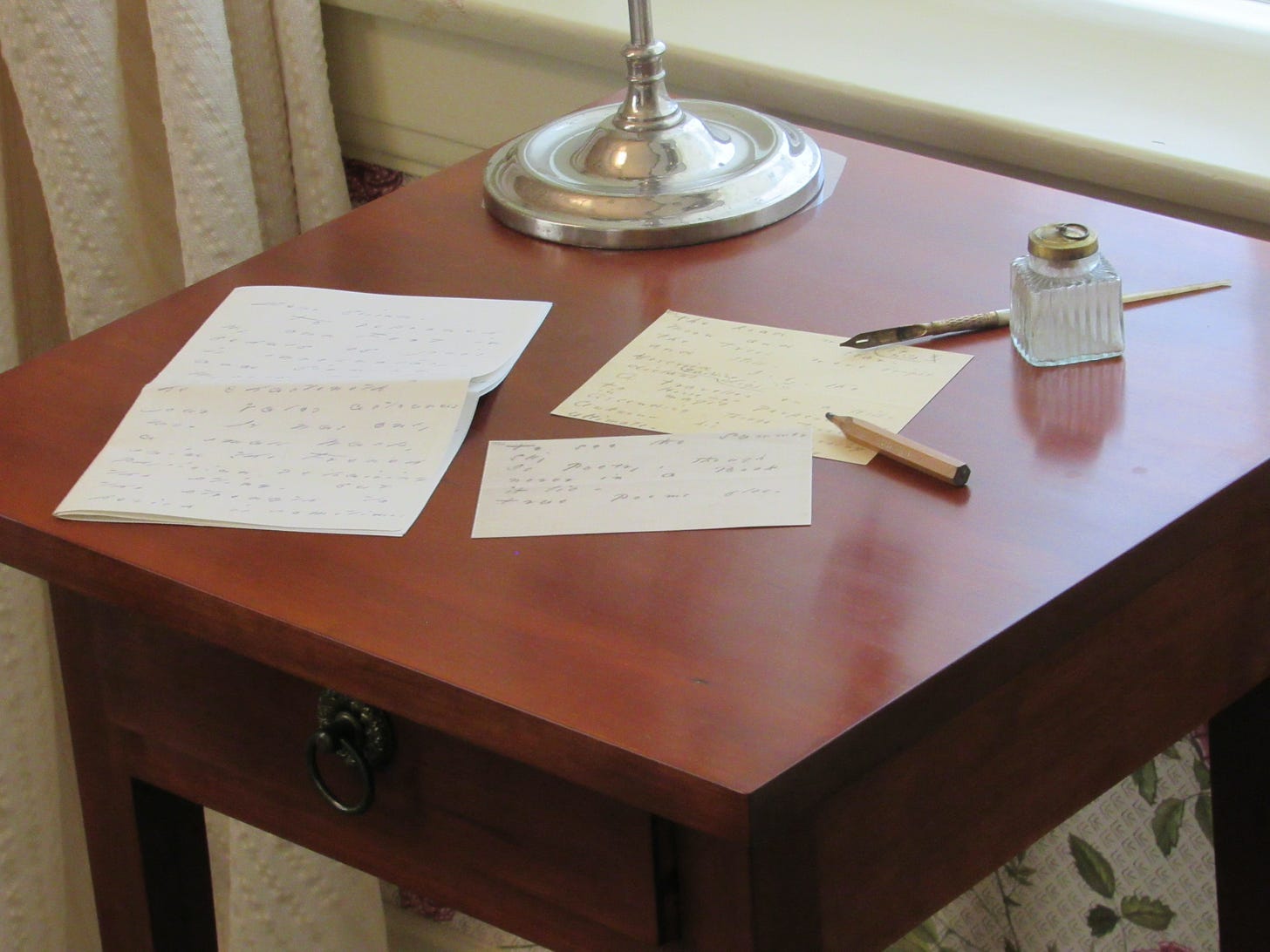

Nothing prepared me for entering her room, her sanctuary, her world for the first time. It was, for me, entering a truly sacred space. To see the postage-stamp desk where she wrote 1800 poems and around 1,304 letters, to see a replica of the white dress she wore and the bed where she died was overwhelming. To know that it looked like the period of Emily’s life when she wrote the most poems.

I thought of how young Emily brought her friend, Maggie, upstairs to this room, closed the door and pretended to lock it with an invisible key. She then turned and told Maggie about her room, “Here is freedom.” For Dickinson, it was. This was where she could plumb the depths of her inner world, often in the late hours of the night while the rest of the family was sleeping.

Despite the myth around her, created after she died to sell her newly published collection of poems, Emily was not a recluse. Instead, she simply socialized with her own select society. She had no time for parties filled with strangers and small talk. I found myself quietly reciting:

The Soul selects her own Society — Then — shuts the Door — To her divine Majority — Present no more — Unmoved — she notes the Chariots — pausing — At her low Gate — Unmoved — an Emperor be kneeling Upon her Mat — I've known her — from an ample nation — Choose One — Then — close the Valves of her attention — Like Stone —

Often her favorite company were trees and her Newfoundland Carlo, named after the pointer of St John Rivers in her favorite novel, Jane Eyre. Carlo was her “shaggy ally.” In a letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, she wrote, “You ask of my Companions. Hills - sir - and the Sundown and a Dog as large as myself that Father bought me -” Her father gave her the dog because he knew he could not stop her from taking long walks in the woods, in the nearby mountains to collect specimens of plants and flowers for her herbarium. There were 424 of them collected just between the ages of 14 and 15.

In a letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, she wrote, “You ask of my Companions. Hills - sir - and the Sundown and a Dog as large as myself that Father bought me -”

She was also known for climbing trees and running. Because of this, her niece and nephews called her Uncle Emily instead of Aunt, as such behavior was not appropriate for women.

She was especially playful with children, perhaps because she never lost her childlike spirit. As she wrote her brother Austin, when Emily was 22, “I love so to be a child. I wish we were always children, how to grow up I don’t know.” I relate to these very lines myself. Yet another connection to me and the poetess.

To be standing here where she spent so much of her time, in a room that is so intimately interwoven with who Dickinson was, I felt her presence. Above her desk where framed portraits of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and George Eliot. The window in front of the desk looked out across to the Evergreens where her brother Austin and his wife, Susan Gilbert Dickinson, lived. Susan who was one of the great loves of Emily’s life and one of the few people she would allow to edit her poems.

I thought of her chestnut colored head leaning over the page as she composed her enigmatic poems. “I know nothing in the world that has as much power as a word. Sometimes I write one, and I look at it, until it begins to shine,” she once wrote. And how her words have shined like beacons since her death. In my own life, it has been there for me, even at my lowest, loneliest of depths. Her poems, like prayers, on my lips.

We were allowed to approach the desk, so long as we stood behind a line in the carpet. To gaze upon this desk, with facsimiles of her poems as if she had just written them and gone downstairs for a moment. To know this is where she got such illuminations, where she wrestled with God, with heaven, with her dreams and desires, with the darkness of death.

I did not want to leave this room. I did not want to go on with the rest of the tour. I longed only to be alone in this room, in the hopes that, perhaps, I might hear her voice speak to me. She had, once, in that poem to me as a child.

I was the last one to leave the room, but not before I whispered, “Thank you, Emily.”

When the tour was over, I returned to the garden. I sat on a bench and wept.

Is this not the power of poetry, of literature? That the voice of one dead for hundreds of years could still speak with such truth that the words resonate within the reader, even when they don’t completely understand. Emily, herself, understood this when she wrote in a letter, “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?”

I sat there on that bench, not wanting to return to the world, wanting only to remain here, to return to her room, to sit there in the silence and the soft golden sunlight that came in through her windows.

Dickinson wrote, “Life is a spell so exquisite that everything conspires to break it.” The exquisite spell of her Eden was one I did not want to be broken and, yet, I found I had to meet a friend for lunch. As I walked back down the drive, to where my car was parked, I glance back at the yellow-bricked Federal Style Revival house and knew that I had been changed, just as I had been when I first opened that collection of her poetry. Emily was still my secret friend, my own personal Saint.

Lovely! Thank you for sharing such a profound and emotionally connected description of your visit. I've been following you for months from Italy. I feel good when I read what you write. It resonates with me.

Grazie mille!

Stefano

So beautiful, Elliott. I'm happy for you that you had this experience; thanks for sharing it with us. I can imagine her presence permeated every corner.